I was part of a meeting on Friday with several members of college leadership, our compensation consultant Christine Riley, Jim Hood, and Natalya Shelkova (from compensation committee).

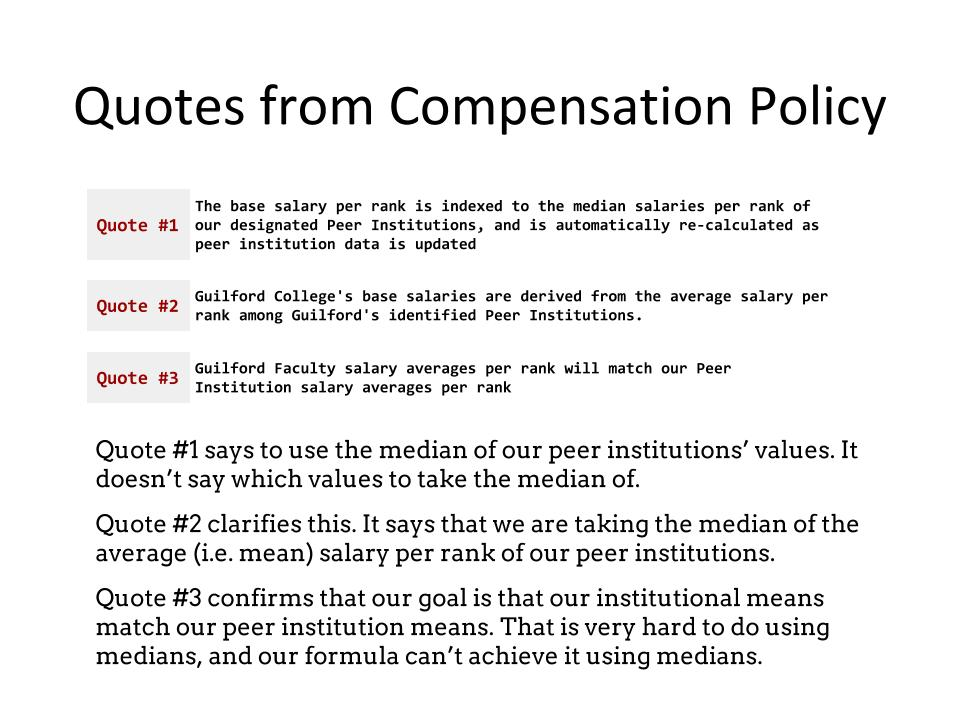

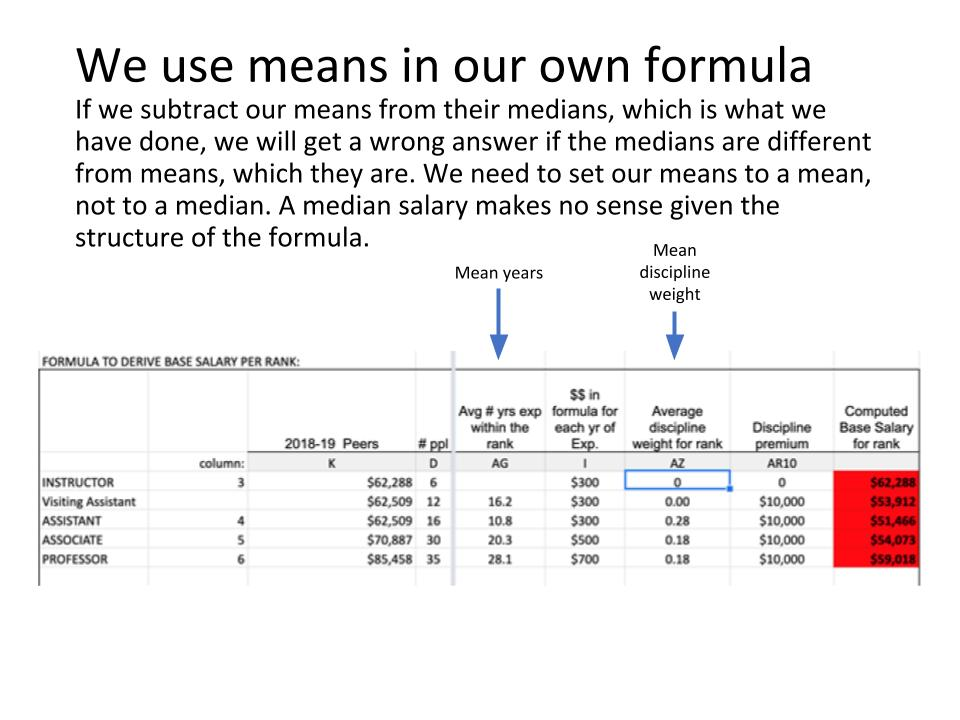

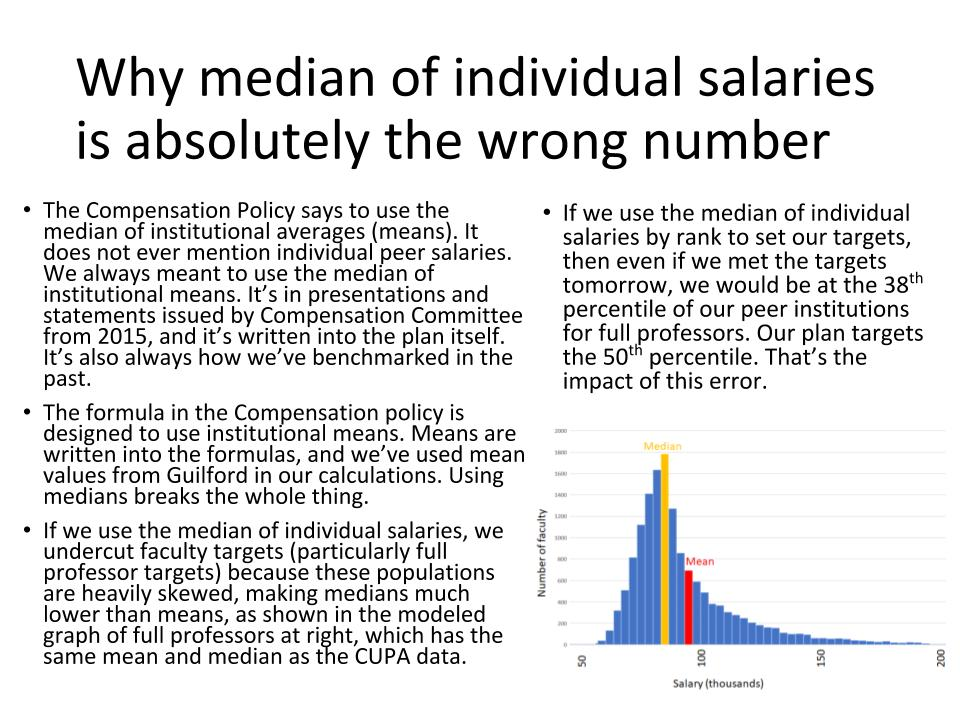

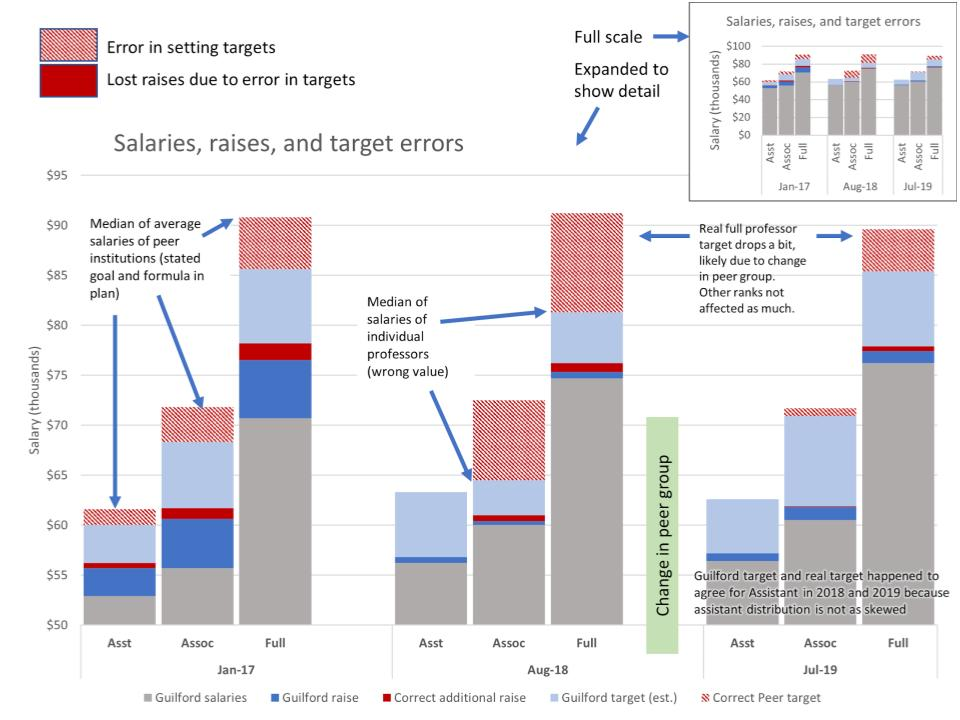

In that meeting, we discussed whether the college has been using the wrong number for setting faculty salary targets over the past three years. We know that in 2018 and 2019, and maybe in 2017, the college used the median of individual salaries of professors at our peer institutions rather than what our policy calls for, which is the median of mean faculty salaries at our peer institutions. Natalya, Jim, and I were in agreement that the median of individual salaries is both (a) not the number specified in the policy, (b) not a number that works in our target formula, and (c) a number that tends to be significantly lower than the number specified in the policy, especially for full professors. I have confirmed this gap by comparing our target salaries for this year, and the CUPA data on which they were based, with the median of peer institutional mean salaries (the number we’re supposed to be using) from AAUP. I shared that information with you around the time of the opening faculty meeting in this document.

In Friday’s meeting, Christine Riley confirmed that the intent of the policy was to use the median of institutional means salaries among our peer institutions, something that the faculty members of Compensation Committee have also confirmed.

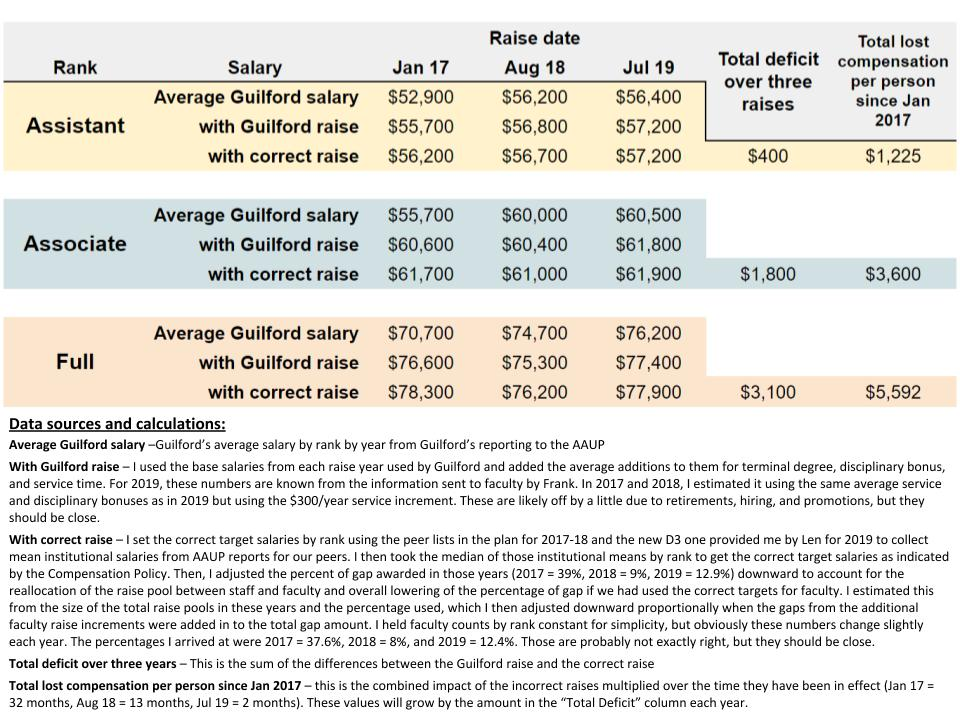

It is clear that for each of the last three raise cycles, our salary targets at most ranks were set too low, sometimes far too low (e.g. ~$7500 for full professors in 2018). We now know that this was not merely bad data, as was cited last year, but instead it was an error in implementation. The outcome of that error has been to deny equitable raises to faculty, particularly to full professors, under the compensation policy. The money that would have gone to faculty has instead been allocated to staff, whose targets were set correctly.

I raised this issue in August 2018, immediately after the raise letters came out with very low targets for full professors. I had the magnitude of the shortfall figured out by September 2018. The college delayed in discussing this until February 2019 and then declined to take any reparative action at all. The only action it took was to change our peer group to a larger and different set of peers. Using a different peer group did not fix the error, and in July 2019, the college again set targets far too low, again without running the salary target numbers through Clerk’s Committee as indicated should be done under the policy. This review by Clerk’s has never happened in the history of the policy, despite being written into it.

In 2018, I did not know that we were asking CUPA for the wrong number. All I knew was that the targets were way too low, and I accepted that it was possible that changing the peer group might help to address what had been very inconsistent and skimpy data from CUPA for 2017 and 2018, although I still felt that the college should do something to correct for the impossibly low numbers it had used in those years.

In July 2019, Jim Hood and I reviewed the raw CUPA data in the human resources office. We discovered that the college was using not just incomplete or flawed data, but had in fact asked for entirely the wrong kind of number from CUPA. It later became clear that it had been using the wrong kind of number for at least 2018 and 2019, and perhaps also for 2017.

At the meeting on Friday, the administrators there seemed to accept that they had made these errors in implementing the salary policy for faculty. I hope they will make a public statement to that effect. After that discussion, which occupied the first half of the meeting, there was some discussion about two concerns. The first was whether the correct institutional data could be delivered by CUPA, and the second was whether using a median of means for faculty targets was fair to staff, whose targets are set based on individual medians.

The first concern, about CUPA data, is largely immaterial – if we cannot get the correct numbers from CUPA, we certainly can from AAUP, which is open-access and much more robust in reporting than is CUPA. CUPA has not served us well in any of the three raise cycles, even setting aside our asking it for the wrong numbers, because they consistently have a small minority of our peer instiutions reporting, and the numbers we’ve gotten from them have varied a great deal (unrealistically so) between years. If we can’t get CUPA to work, we can just use AAUP.

The second concern, about potential fairness questions between faculty and staff, is also immaterial, at least for the past three raise cycles. The college’s compensation committee, comprised of faculty and staff, agreed on this policy. The college published it and implemented it, but it then used incorrect numbers that significantly undercut faculty raises and compensation, three times. That is a wrong that should be righted, and I believe it to be legally actionable, although I hope we do not need to go that route.

Even if the second concern (fairness) doesn’t matter for the past three raises, it does matter for the future of the policy, because we want the faculty and staff formulas to be fair, and we want both groups of employees to reach equitable peer targets. However, I actually don’t think staff salary targets would change much if they were based on medians of institutional means rather than medians of individuals. This is because there are many, many kinds of staff positions, and most of them are unique or in very small numbers at institutions our size. Therefore, a median of individuals will be essentially the same as a median of institutional means for these positions. This is in contrast to faculty positions, where there are only four ranks we track, and they contain many faculty, who are often in those ranks for a long time, with salaries that can vary by tens of thousands of dollars at Guilford (or even by hundreds of thousands at some of our peers). I would be happy to check my prediction here if I am given the data to work with, but my sense is that there is no fairness issue in this area. Regardless, we should have followed the policy we have on the books, and we should keep following it correctly until we agree to change it. The fairness issue is, I think, a red herring at this point, given that we had a policy and didn’t follow it in a way that was already unfair.

I don’t know what happens now. It’s my strong feeling that something should be done to repair the harm caused by this error, and that the repair should be more significant and more immediate than just “we’ll do better in the future,” because all tenure-track faculty have been and continue to be negatively impacted. I would like to talk to people about what the nature of that repair should be, because while I can represent the math well, I have no current role in representing the faculty.

I am attaching five slides I prepared for the Friday meeting which lay out the argument I made. Natalya also prepared slides on the median/mean issue and discussed it very effectively. If you need help interpreting what I’ve got here, please ask questions in the comments. There’s a caption under each slide that gives some context and guidance.